Decoding Kaggle’s 2023 AI Report: Essential Tips for Machine Learning with Tabular Data 🔍📈

Published:

It’s difficult for us to stay on top of the latest AI advancements with 100s of research papers, articles, and newsletters published daily. Luckily, Kaggle has recently published their annual AI report earlier this month, which distills and summarises the latest advancements this past action-packed year.

The Kaggle AI Report 2023 collates the best 3 essays on 7 important AI topics: (1) Generative AI, (2) text data, (3) image & video data, (4) tabular / time-series data, (5) Kaggle competitions, (6) AI Ethics, and (7) Other (for topics that do not fall neatly under the previous 6 areas). All essays are fascinating reads, jam-packed with information. Some essays provide a comprehensive overview of a topic, other essays dive deep into the technicalities, and other essays leave you with thought-provoking ideas on what the future may entail.

For this blog post, I’ll focus on tabular and time-series data (in the context of machine learning (ML) competitions) since this is the most common data type that data scientists face and has the highest applicability/utility. As Bojan Tunguz said:

“It is estimated that between 50% and 90% of practicing data scientists use tabular data as their primary type of data in their primary setting.”

To supplement my takeaways on best practice for tabular data, I’ll also draw on the findings from ML Contests’ State of Competitive Machine Learning Report published earlier this year, which broadly aligns with Kaggle report. I’ll write up on the latest advancements on the other AI topics in future blog posts.

DALL-E generated image of a researcher flooded by academic papers

Why learn from ML competitions winners?

There is great value in analysing winning solutions of ML competitions. Competitions act as a battleground for participants to test out the latest research models and architectures. Or as ML Contests puts it:

“One way to think of competitive machine learning is as a sandbox for evaluating predictive methods.”

Competitions become more useful over time as we can see trends on which ideas work, as teams incorporate techniques from winning solutions from previous competitions into their own - forming new baselines. Two great resources for reading competition write-ups by winners are DrivenData’s blog and Kaggle discussions. Following these discussions is a useful proxy of staying on top of the latest practical advancements.

However, do take some of the learnings with a pinch of salt

Learning how to improve a model’s performance by a few decimal points may have a positive impact to a company’s bottom line, especially if it serving millions of customers. However, there does come a point of diminishing returns when trying to eek out that extra .0001 of performance, depending on the business context. Because of the iterative nature of ML, it can be difficult to decide when “good” is “good enough”.

Whilst machine learning competitions do push advancements in AI, the focus does not fully translate to the real-world professional setting. With the growing importance of AI ethics, many are concerned with the integrity and fairness of machine learning-based systems, services, and products.

Since models are judged by their performance in competitions, a metric that is easily quantified, understood by competitors, and the determinant of the ranking for prizes and accolades - it becomes the main focus. This means a result-first approach rewards black-box approaches which do not consider explainability and interpretability. This is particularly relevant for ensembling, more on that later.

However, I still believe using the consensus of the ML community acts as a useful starting point. As it is very easy to get bogged down by analysis paralysis when there are thousands of models, tools, and packages to choose from.

Common themes from the winners of tabular / time-series data competitions

There are a number of common themes that regularly appear amongst winning solutions of ML competitions, across various domains such as finance to healthcare. These themes agree with findings of academic literature too which have studied these competitions. These themes include the importance of:

- Feature engineering

- Cross-validation

- Gradient Boosted Decision Trees

- Ensembling

Feature engineering is still a crucial part of the ML modelling pipeline

Feature engineering is the process of creating, selecting, and transforming variables to maximise their predictive power in models. It’s a dynamic, iterative, and highly time-consuming process. Feature engineering is well recognised as being one of the most important, if not the most important, part of a tabular ML modelling pipeline, for both competitions and industry. Feature engineering is especially important for tabular data compared to deep learning techniques for computer vision tasks, where data augmentation is more focused on.

In Rhys Cook’s winning essay they provided two great competition examples to illustrate how varied feature engineering approaches can be:

- Amex Credit Fault Prediction (the most popular ML competition of 2022 with 5,000 teams entered, likely due to the growing scarcity of tabular Kaggle competitions and the $100k prize pool)

- AMP Parkinson’s Disease Progression Prediction

In Amex Credit Fraud Prediction competition, the 2nd place solution team used a brute force feature engineering approach. Where they created thousands of features, such as aggregations, differences, ratio, lags, and normalisation, based on the original 190 features. Then the team applied extensive feature selection techniques: (1) removal of zero importance features, (2) stepped hierarchical permutation importance, (3) stepped permutation importance, (4) forward feature selection, and (5) time-series cross-validation, to obtain the final subset of 2,500 features.

For the Parkinson’s Disease Progression Prediction competition, the 4th place solution team realised that the curse of dimensionality applied to this dataset - as there were 1,195 features for proteins and peptides for only 248 patients in the training set, across 17 patient visit dates. This dataset had sufficient train data to train only 25 features. As a result, they focused on creating features based on the patient visit dates, rather than the protein/peptide features which were the main focus of the competition. The top 18 teams noticed that features based on patient visit dates had the best predictive ability.

However, Cook found that there is not much academic literature on the topic of feature engineering. This the lack of research is likely due to the fact that feature engineering is very specific to the problem and dataset, and requires creativity and flexibility, and therefore is difficult to generalise.

Despite this, there are resources which provide useful guidance for many domain applications, such as the Feature Engineering and Selection book. There are automated feature engineering solutions available such as Featuretools and others. However, most competitors tend to do it manually.

Robust cross-validation to trust the model results

Cross-validation (CV) is the process of evaluating a ML model and testing its performance. By training on only a subset of the training data, and measuring performance on the remaing datam we can understand how well a model generalises. It allows data scientists to know if the model is reliably improving model performance rather than overfitting to the test dataset (or public leaderboard (LB) for ML competitors).

In fact, it is common for competitors to select a final model that underperforms according to the LB but has more robust CV, in the hopes of generalising better against the private test data. However, good performance is not guaranteed on the holdout / test set, as it may be taken from a different distribution.

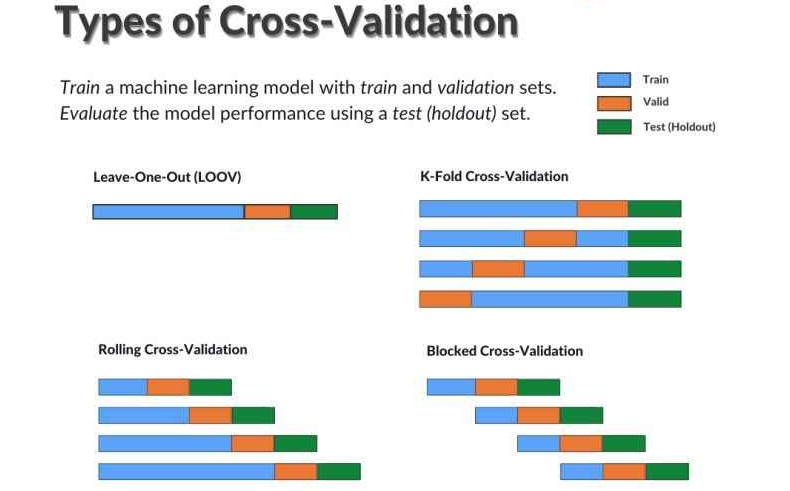

There are two general approaches to cross-validation:

- Simple train/test split (or Leave-one-out CV (LOOCV)): Where you take split your shuffled training data into two splits, for example 80% for training and 20% for testing.

- k-Fold Cross-Validation: Where you split the shuffled data into k-equal groups, or folds. The model is trained k times, where one of the folds is excluded as a test set and the remaining folds are trained on, using the excluded test set to evaluate the model performance. After each evaluation, the evaluation score is retained and the model is discarded. After the training, the skill of the model is summarised using the sample of model evaluation scores.

k-fold cross-validation is the typical go-to CV scheme of choice for ML competitors, despite being more computationally intensive than the first method. There are many different types of k-fold CV strategies available, depending on the skew of the target variable (standard, stratified, stratified in groups, and multi-label stratified) and if the data is time series which will require time-series cross-validation, such as rolling CV or blocked CV.

Types of cross-valiation (Source)

Gradient Boosted Decision Trees are still beating Deep Learning models for tabular data

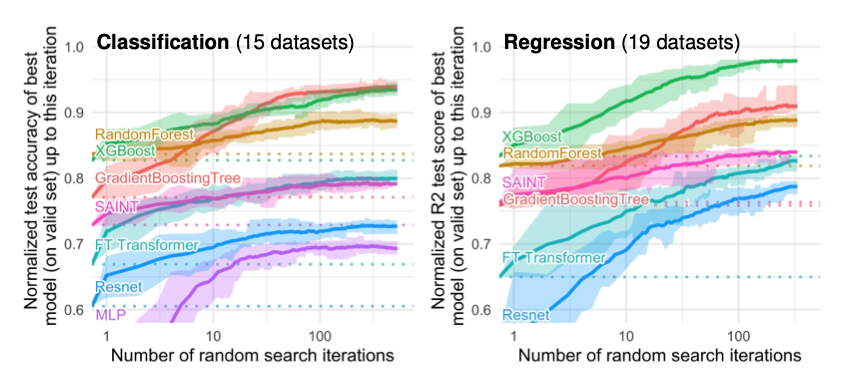

Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT), or also known as Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT) or Gradient Boosted Machines (GBM), are the go-to family of traditional ML models for tabular data. GBDTs even outperform deep learning (DL) models which were purpose built for tabular data, especially when performance is averaged across multiple datasets.

Quick Recap on Gradient Boosted Decision Trees

GBDTs are a ML ensemble method that constructs a strong predictive model by combining weak learners, decision trees. The algorithm operates iteratively where each new tree corrects the errors made by the existing ensemble of trees. They are used for both classification and regression tasks.

The three main GBDT models are:

- XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting): Introduced in 2014 by Tianqi Chen and has been a staple of ML competition winning solutions the past 9 years (this repo shows some of the many winning XGBoost solutions). Unlike standard Gradient Boosting, which starts by growing a full tree before pruning, XGBoost prunes the trees depth-first, which is more efficient. XGBoost also has inbuilt mechanisms for:

- L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization to reduce model complexity and overfitting

- Handling missing values

- Efficient k-fold cross-validation

- LightGBM (Light Gradient Boosting Machine): Introduced by Microsoft in 2016, LightGBM offers some benefits over XGBoost - having leaf-wise tree growth, instead of tree-level growth. This means that algorithm will choose the leaf that will reduce the most loss, rather than making all leaves in the tree level grow - resulting in more compact trees.

- CatBoost (Categorical Boosting): Introduced by Yandex in 2017, CatBoost can handle categorical features without pre-processing like one-hot encoding.

According to ML Contests, LightGBM was the the most used GBDT library in 2022 ML competitions - mentioned in 25% of write ups or in their questionnaire, which is the same amount as CatBoost (second most used GBDT library) and XGBoost combined. Although this may change with the newly updated XGBoost 2.

](/images/blog/2023-10_GBDT-Packages.png)

Top GDBT packages, image taken from MLcontests

What does the research literature have to say on the debate?

There have been many papers that have compared these two broad groups of models and have come to the similar conclusions. In Tabular Data: Deep Learning is Not ALl You Need (2021), Shwartz-Ziv and Armon compared XGBoost and DL models for tabular data and found that XGBoost performed better than most DL models across all datasets, but typically a specific DL model would perform better at a specific dataset. They highlighted that XGBoost requires significantly less hyperparameter tuning to achieve good performance, which is important in the real-world setting.

From the paper Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on tabular data (2022), Grinsztajn, Oyallon, and Varoquaux found that this phenomenon is especially true for medium-sized datasets (around 10k training examples) but the gap between tree-based models and deep learning lessons as dataset size increases (around 50k training examples). Also, tree-based models are more robust against uninformative features, as they process features independently, whereas deep learning methods are more prone to overfitting to noise.

Benchmark performance comparisons between GBDTs and deep neural networks, taken from Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on tabular data (2022)

All that being said, neural networks can provide benefits if the tabular data has some underlying structure well suited for neural network architectures, such as sequenced or hierarchical data. For example, the famous time-series M-competitions have recently been dominated by deep learning models. This blog post and paper by Amazon Research are great starting points to get a comprehensive overview on the pivotal advancements in DL for tabular data and time-series, respectively.

Ensembling for performance gains

Although deep learning has not replaced GBDTs for tabular data, they do provide value when ensembled with boosting models. Ensembling is when multiple different machine learning models are combined to improve the overall prediction performance. This works best when diverse models are combined as collectively they can offset each other when individual models make uncorrelated errors.

Almost all competition winning solutions involve a large ensemble of models, rather than a single model (although it does happen rarely). Kaggle is known as an ensembling playground, where participants will ensemble many different models to improve their score. However, this comes at a cost of computational resources, complexity, explainability, and inference time - which are important considerations in a real-world applications.

Model outputs are typically ensembled / aggregated by:

- Averaging (or blending): This is the simplest method of ensembling, options include averaging, weighted average (most common method), and rank averaging.

- Voting: For classifications tasks, models can vote on the prediction. The most common option is majority voting, where class is predicted by the selection of the majority of models.

- Bagging, boosting, and stacking:

- Bagging (short for bootstrap aggregating) is when you sample with replacement to create different datasets called bootstraps and then a different model on each of those bootstraps, and then aggregate the results - by averaging for regression or voting for classification.

- Boosting is a family of iterative optimum algorithms that converts weak learners to strong learners. Each learner in the ensemble is trained on the same set of samples but samples are weighted based on how well the ensemble classifies them.

- Stacking is the process of training base learners from the training data and then create a meta learner that combines the output of the base learners to output final predictions.

Conclusion

It’s difficult staying on top of the latest advancements in AI and ML but the Kaggle AI Report 2023 and the State of Competitive Machine Learning Report provide invaluable insights, especially for tabular and time-series data. This blog post highlighted the continued importance of feature engineering and robust cross-validation, the unassailable effectiveness of GBDTs over DL models for tabular data, and the power of ensembling to improve performance.

However, it is important to recognise that competition settings has nuances and different priorities that does not directly translate to real-world applications, especially with the growing importance of explainable AI. In reality, you most of your time will likely be on data cleaning or converting your notebook code into production with MLOps (a topic I’ll cover in future).

Thanks for reading if you’ve made it this far, I hope you’ve found it useful!